Airway assessment: If you’ve ever stepped foot in an operating room or an ER, you know that the first rule of anesthesia is “protect the airway.” But how do we know which patients will be a “straightforward tube” and which ones might keep us up at night? One of the most enduring tools in our bedside arsenal is the Modified Mallampati Test (MMT). It’s quick, non-invasive, and—when done correctly—gives us a vital “clue” into the anatomy we’re about to encounter.

Why the “Modified” Version?

The original test was developed by Dr. Seshagiri Mallampati in 1985. However, the version we use today is actually the Samsoon and Young modification from 1987. They realized that the original three-class system didn’t quite capture the most difficult cases, so they added “Class IV” to identify patients where the soft palate is completely hidden.

The Anatomy of the View

The MMT works on a simple premise: the size of the base of the tongue is inversely proportional to the space in the oropharynx. If the tongue is massive relative to the mouth, it will obscure your view of the uvula and, eventually, the glottis during intubation.

How to Perform the Test (Avoid Common Mistakes)

Believe it or not, the Mallampati score is often recorded incorrectly because of poor technique. To get a “true” grade, follow these steps:

- Posture Matters: The patient must be sitting upright. Assessing a patient while they are supine (lying down) can significantly change the soft tissue distribution and give you a false reading.

- No Phonation: This is the most common error. We often tell patients to “say Ahhh,” but phonation actually lifts the soft palate, making a difficult airway look easier than it actually is.

- The Tongue: Ask the patient to open their mouth as wide as possible and stick their tongue out as far as they can.

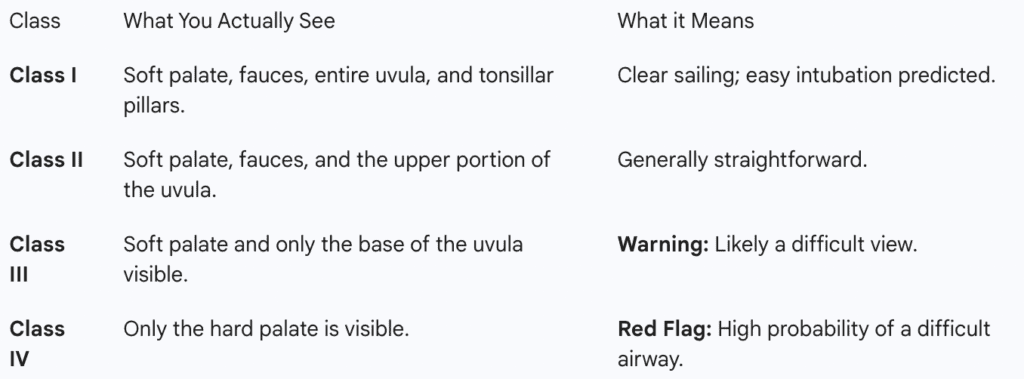

Breaking Down the Classes

We categorize the view into four distinct classes. Think of it as a sliding scale from “Wide Open” to “Completely Obstructed.”

Is Mallampati Enough?

In a word: No.

While the MMT is a great screening tool, it isn’t a crystal ball. Research shows that it has a high “false-positive” rate. This means a patient might look like a Class IV but be a relatively easy intubation, or a Class II might surprise you with a Grade 4 view on laryngoscopy.

To stay safe, most clinicians use the LEMON acronym, where Mallampati is just the “M.” You still need to look at neck mobility, the “3-3-2” rule for jaw/neck distances, and any potential obstructions like tumors or trauma.

The Bottom Line

The Modified Mallampati Test is a classic for a reason. It’s a 10-second test that forces us to look closely at a patient’s anatomy before we ever induce anesthesia. It isn’t perfect, but in a field where surprises are rarely good, it’s an essential part of being prepared.

Further Reading & References

- Mallampati SR, et al. A clinical sign to predict difficult tracheal intubation. Canadian Anaesthetists’ Society Journal. (The foundation of airway assessment).

- Samsoon GL, Young JR. Difficult tracheal intubation: a retrospective study. Anaesthesia. (The birth of the 4th Class we use today).

- Lee A, et al. A systematic review of the Mallampati tests. Anesthesia & Analgesia. (A sobering look at the accuracy and limitations of the test).