Introduction

A nerve injury can significantly impact motor, sensory, and autonomic functions, leading to pain, weakness, or paralysis. Understanding the anatomy of peripheral nerves and the Seddon classification (neurapraxia, axonotmesis, neurotmesis) helps in diagnosing and managing these injuries effectively. Whether caused by trauma, pressure, or laceration, nerve damage varies in severity—some cases heal naturally, while others require surgical intervention.

Anatomy of a Peripheral Nerve

Nerve Structure and Function

A peripheral nerve consists of:

- Cell body (soma) – Receives incoming signals via dendrites.

- Axon – Transmits electrical impulses to target organs.

- Myelin sheath – Insulating layer formed by Schwann cells, enhancing signal speed.

- Nodes of Ranvier – Gaps in the myelin sheath where depolarization occurs, enabling rapid saltatory conduction.

Bundles of axons form fascicles, surrounded by perineurium, while multiple fascicles are encased in the epineurium to form a complete nerve.

How Nerves Get Injured

Nerves can be damaged by:

- Contusion (blunt force trauma)

- Pressure (e.g., nerve entrapment)

- Traction (stretching, as in dislocations)

- Laceration (complete severing)

A common example is “Saturday night palsy,” where prolonged pressure on the brachial plexus causes temporary dysfunction.

Classification of Nerve Injuries

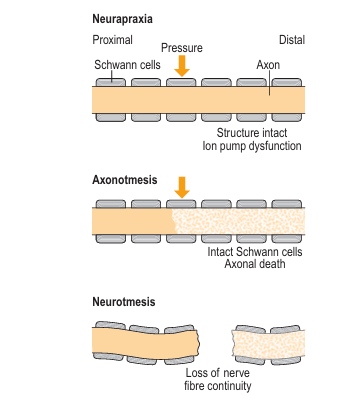

The Seddon classification divides nerve injuries into three types based on severity.

1. Neurapraxia (Mild Nerve Injury)

- Cause: Temporary ischemia due to pressure or contusion.

- Effect: Ion pumps fail, blocking nerve signals.

- Recovery: Full function returns once pressure is removed (hours to weeks).

- Example: Wrist drop from radial nerve compression.

Note: The correct term is neurapraxia (Latin for “nerve not working”), not “neuropraxia.”

2. Axonotmesis (Moderate Nerve Injury)

- Cause: Axon damage (e.g., severe crush or stretch).

- Effect: The distal axon degenerates (Wallerian degeneration), but the myelin sheath remains intact.

- Recovery: Axons regrow at 1 mm per day along the myelin sheath. Tinel’s sign (tingling upon tapping) helps track regeneration.

- Outcome: Often incomplete due to scarring.

3. Neurotmesis (Severe Nerve Injury)

- Cause: Complete nerve transection (e.g., knife wound).

- Effect: No spontaneous healing; axons grow randomly, forming painful neuromas.

- Treatment: Requires surgical nerve repair (epineural suture).

- Outcome: Partial recovery due to misrouted axons and scar tissue.

Diagnosing and Treating Nerve Injury

Clinical Assessment of nerver injury

- Electromyography (EMG) & Nerve Conduction Studies (NCS) – Measure electrical activity.

- Tinel’s Test – Checks for regenerating nerves.

- MRI/Ultrasound – Identifies structural damage.

Treatment Options for nerve injury

- Neurapraxia: Rest, avoid pressure.

- Axonotmesis: Physical therapy, monitoring regeneration.

- Neurotmesis: Microsurgical repair or nerve grafting.

For more details, see this Wikipedia article on nerve injury.

Recovery and Rehabilitation

- Physical therapy prevents muscle atrophy.

- Electrical stimulation may aid nerve regrowth.

- Pain management (e.g., gabapentin for neuropathic pain).

According to a study in Journal of Neurosurgery, early surgical intervention improves outcomes in neurotmesis.

Conclusion

Understanding nerve injury types—neurapraxia, axonotmesis, and neurotmesis—helps in accurate diagnosis and treatment. While mild injuries heal on their own, severe cases need prompt medical attention. If you suspect nerve damage, consult a specialist for proper evaluation.

For further reading, explore this NIH guide on peripheral nerve repair.

Have you experienced nerve injury recovery? Share your story below!

Also Read: Orthopedics Surgery Topics